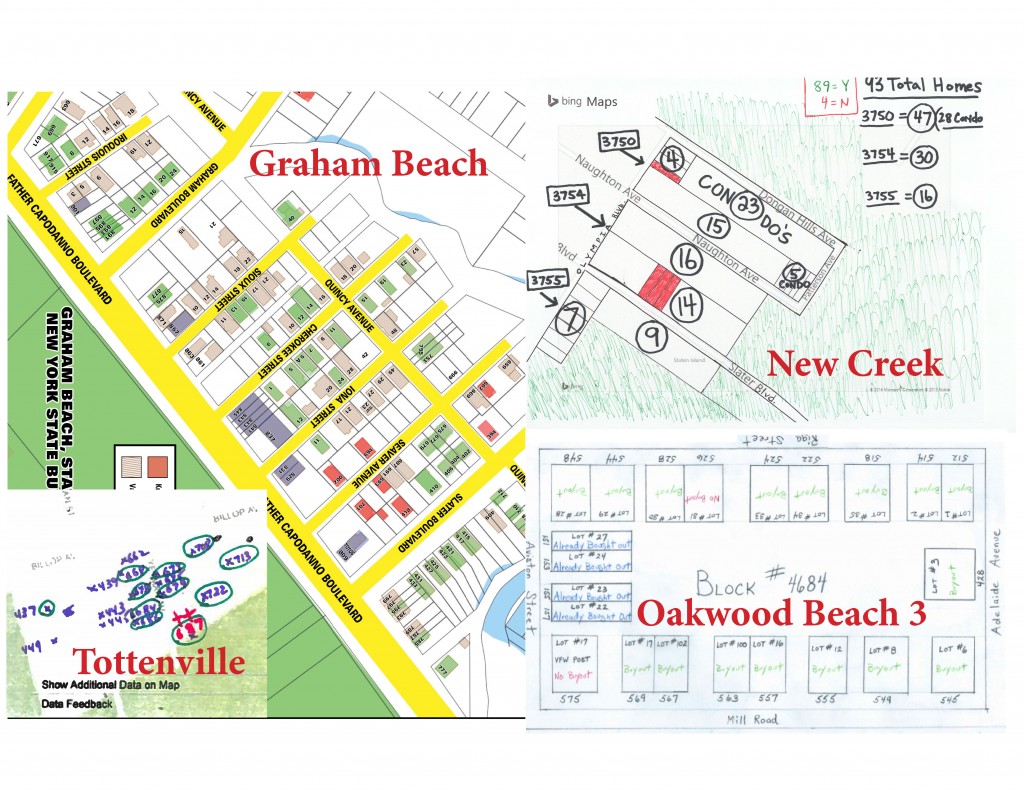

These are the next 4 proposed areas to receive a buyout from the State, as submitted by their respective community leaders, and assisted by Joseph Tirone Jr. These areas all have petitioned the State as a result of a history of serious flooding and were all hit particularly hard by Sandy. Each community has presented their case in an organized fashion, with community members united in their cause for a State buyout. The properties in each neighborhood are contiguous, and returning them to nature would create a natural barrier from future storm surges, as required by the Governor’s enhanced buyout program:

Posted on:

September 9, 2013

May 01

Hurricane Sandy Buyouts Cause Storm Of Confusion, Worry From Politicians by David Howard King

ALBANY, N.Y. — The Fox Beach community of Staten island sits only a few blocks from the ocean on wetlands where tall reeds sprout across the landscape.

After the lives of three of its residents were lost during Hurricane Sandy and flooding destroyed a number of the small bungalows that make up the community, more than a few people who live in Fox Beach were ready to abandon the previously idyllic area.

A few days after the storm, a large group of local homeowners began meeting in the St. Charles School auditorium to discuss how to move forward and, when the prospect of government buyouts was brought up, the room was casually polled.

“Every person in that auditorium raised their hands,” said Joseph Tirone, who owns a home in Fox Beach and is the head of the Oakwood Beach Buyout Committee. He said the homeowners pressed officials for weeks, and eventually caught the attention of Gov. Andrew Cuomo.

Cuomo announced on Feb. 25 that the Fox Beach community, which is a subsection of the larger Oakwood neighborhood, would be the testing ground of his general buyout program designed to return parts of the seashore to a natural state to create a storm buffer.

“There are some places that Mother Nature owns,” Cuomo told the audience at the College of Staten Island. “She may only come to visit every two years or three years or four years. But when she comes to visit, she reclaims the site.”

Weeks later, the buyout program is coming into focus for the Fox Beach community, but what will happen with the rest of storm-ravaged New York is still hazy. For months, homeowners have heard sometimes conflicting reports about the city’s plans, the state’s plans, as well as programs offered through the Federal Emergency Management Administration.

Lawmakers and community members say they have been told that the state under Cuomo will be unveiling a number of “enhanced areas” in the next few weeks where homeowners will be able to apply for a buyout worth 100 percent of their homes pre-storm value, with a five percent incentive if they move within their borough. The Cuomo administration has yet to confirm.

The state has allocated $171 million for buyouts, but officials estimate they could ultimately spend $400 million. Officials estimate 10,000 homes were severely damaged during Hurricane Sandy but expect only 10 to 15 percent of owners will take buyouts.

Meanwhile, the Bloomberg administration is not billing its efforts as a “buyout” program and will refer those looking for buyouts to the state.

Instead, the Bloomberg administration has also proposed a program that, if approved by U.S. Housing and Urban Development, will allow the city to buy damaged property at post-Sandy rates for redevelopment. The city’s program would appeal to property owners who aren’t part of the “enhanced areas” that would be covered under the state.

City officials say the properties would first be offered to homeowners who are staying and might want a larger yard, or to add to their property. It is unclear exactly how much the city plans to spend on this program.

Staten Island Borough President James Molinaro says his office has received 400 inquiries about home buyouts but is unsure how the programs offered by the city and state will help.

“Almost every block is a different story, every home has a different problem,” Molinaro said. “Some of these people are already underwater on their mortgage.”

Molinaro said it is unclear how those homeowners would benefit from a buyout if the money they get from the city or state does not cover their mortgage and they are left without a home.

He noted, however, that some banks in New Jersey have been working with homeowners to come to mutually beneficial solutions.

“I wouldn’t say there is an easy answer, but it is a problem we are aggressively addressing,” Tirone said. He said he expects banks to work with homeowners who are underwater on their loans and who want to take a buyout.

The press and local officials have underestimated the desire for buyouts, he said. “Elected officials are opposed to buyouts because they can’t visualize unbuilding,” said Trione, who feels city lawmakers have failed to do enough to ensure local homeowners are briefed on all their options.

Tirone recalls the story of a retiree who had tapped out his life savings to make repairs to his house following Sandy. “If he had been made aware that he could get the pre-storm price for his house and buy a new house that is not in a storm zone, he could have been set for life with his savings still intact,” Tirone said.

Molinaro is skeptical of the process so far, saying, “I have not seen any movement yet. The governor said he would buy homes at 100 percent of their value pre-Sandy but I have not seen any purchased yet.”

He emphasized that he has advocated for prioritizing buyouts to homeowners who have completely lost property and who have no mortgage so that they can quickly purchase a new home. Molinaro said he had warned residents that the buyout process can take years.

Randy Douglas, Town Supervisor of Jay, N.Y., knows firsthand that the government buyout process is anything but quick.

The Town of Jay suffered flooding in 1996 and 2008 from the AuSable River; then, in 2011, Hurricane Irene hit and the flooding was worse than ever. Roads, parks, youth facilities and sewer systems were wiped out along with homes. The town nearly lost its iconic covered bridge.

Some residents had simply had enough. Eighty homeowners out of the town’s estimated 2,500 residents were interested in a buyout program — one that paid 75 percent of pre-storm value.

Eighteen months later, residents are just now signing contracts with FEMA for the purchase of their properties. And the number of interested homeowners has dropped to 40.

”Some of them just couldn’t wait due to the length of time,” Douglas said. “A two-year process is way too long. I actually had people pass away during the process. It is just really sad.”

Douglas said he hopes that the concerns of victims of Irene and Lee have helped push officials to expedite the process for other homeowners. (The good news for Douglas: the state has included funds in its Sandy recovery plan to make sure homeowners who are bought out from Irene and Lee get a full 100 percent of their homes’ pre-storm value).

Despite having advocated for buyouts and having helped his residents push through the process, Douglas said there isn’t anything terribly positive about seeing residents decide it is time to pack it up.

“I’ve said since day one this isn’t a good thing,” he continued. “You lose your tax base, you lose families who have lived here for generations and you lose your identity. But with us, we couldn’t continue to put people in harm’s way.”

Douglas said he understands the reluctance of New York City officials to fully back buyouts. “Mayor Bloomberg has said he wants to build back stronger and seems to want to avoid buyouts. I’m not criticizing him because you don’t want to lose these people. You don’t want to give them up,” he said.

Sen. Joe Addabbo of Queens, who represents some of the neighborhoods hardest-hit by Sandy, including Breezy Point where dozens of homes went up in flames, said he has not seen a great deal of interest in buyouts. “We have a lot of longtime homeowners whose families have been here for generations who just want to rebuild. They aren’t looking to go somewhere else,” Addabbo said.

Addabbo acknowledged, though, that there has been confusion about buyouts. “Whenever there is a lack of information there is confusion,” he said, “but I think it will end as we get more information on the two programs in the next two weeks.”

But Addabbo admits he doesn’t favor buyouts — in fact, he thinks they are a bad idea. “Personally, no, I don’t buy into the buyout program so to speak. It is a loss of revenue for the city, and the neighborhood behind that neighborhood loses their storm buffer, I think it causes other problems,” Addabbo said.

The state senator said not enough is being done to address flood mitigation. “What about seawalls, jetties, things that mitigate flood damage? Why aren’t we talking about that? Instead we are gonna buy ’em out? I don’t want them to leave,” he said. “As an elected official I want them to stay. Whether they have to elevate or [do] flood mitigation — whatever it takes.”

The Fox Beach community of Oakwood was labeled an “enhanced area” where the entire neighborhood was eligible for a buyout. Of the 183 households that were eligible for the state program, 180 have submitted applications according to state officials. Those homeowners are eligible for 100 percent of their homes pre-storm value.

Tirone said he thinks Cuomo’s motivations are completely apolitical. “I truly believe this plan has nothing to do with politics. The governor wants to create a natural buffer for those inland,” he said.

Meanwhile, plans for his neighborhood are developing apace. Homes have been appraised and, although he thinks Cuomo might be unhappy with him for such a bold prediction, he speculated that the process could be completed before the end of the year — a notable accomplishment given that the federal process can take three to five years at times.

But, for now, Tirone is still helping get the word out about the state program. “I get five to 10 calls a day from residents asking me to help them get bought out,” he said.

Image of destroyed home in Oakwood, Staten Island, by Paul Soulellis, used under Creative Commons license.

Source:

http://www.gothamgazette.com/index.php/housing/4233-hurricane-sandy-buyouts-cause-storm-of-confusion-worry-from-politicians?tmpl=component&print=1

Nov 17

After The Waves, Staten Island Homeowner Takes Sandy Buyout

Stephen Drimalas stands outside his former home in Staten Island’s Ocean Breeze neighborhood. He rebuilt his home after Superstorm Sandy but recently decided to sell it to the state of New York.

Jennifer Hsu/WNYC

Two years after Superstorm Sandy struck the Northeast, hundreds of Staten Islanders are deciding whether to sell their shorefront homes to New York state, which wants to knock them down and let the empty land act as a buffer to the ocean.

Stephen Drimalas was one Staten Islander faced with this tough decision. He lived in a bungalow not far from the beach in the working-class neighborhood of Ocean Breeze. He barely escaped Sandy’s floodwaters with his life.

“I had to speed outta here,” Drimalas said. “Another minute or two and I wasn’t getting out. That’s how fast it came in.”

He was folding laundry before he fled. And when he came back the next day, the clothes were there on the top of his bed, but the bed was floating in water. He slept in his car on cold nights — before the FEMA check showed up — because he couldn’t afford a motel room.

He fought with his insurance company, and when that money finally came through, he rebuilt his severely damaged home. A year after Sandy, it sounded like he’d be staying.

“This was a freaky thing that happened,” he said. “It was a superstorm; it was a perfect storm. So I don’t think we’ll ever get another one again in my lifetime.”

But about a third of his neighbors never came back. And when the city tore down several condemned homes, his block started looking gap-toothed and forlorn.

He wondered, “What if I wanted to move? Who’d pay money for a house in a flood zone?”

And Drimalas was still spooked from the night the storm rushed in.

“You know what happened, a couple of weeks ago, we had bad weather, and you hear the wind howling and everything like that,” he said. “Then you start thinking, ‘Uh oh, is the water coming again?’ You know? It goes through your mind now ’cause, you know, it’s in your head.”

Then New York state offered to buy his home as part of program to get people out of dangerous areas likely to flood again. And after thinking it over, Drimalas took the deal. In the past two years, he’s cycled through all the emotions of the victim of disaster: grief, fear, anger, defiance. But now there’s a new one: contentment.

“And little by little, they’re moving out,” Drimalas said. “You’ll start seeing more and more U-Haul trucks here. People just want to go.”

The state will spend about $200 million to purchase land in Ocean Breeze and two other Staten Island neighborhoods. That’s about 550 acres of waterfront property in New York City that now faces an extremely unusual fate: permanent abandonment.

“We are going to demolish the homes,” said Barbara Brancaccio, a spokeswoman for Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s Office of Storm Recovery.

“Essentially, they go back to nature,” she said. “We didn’t bring this possibility to the community. The community came to us and said, ‘We want to go.’ ”

But a handful of people are planning to stay. Brancaccio says that a year from now, those holdouts can expect their neighbors to be rabbits, raccoons and wild turkeys. Drimalas says it’s happening already.

“You know what [I saw] in my yard the other day? A muskrat,” he said.

Drimalas is preparing to relocate to his Florida condo. It’s 2 miles inland and 30 feet above sea level. Right now he’s selling or giving away his stuff, including a really big barbecue grill.

“My family’s going to come take whatever they want first, whatever they need, and then I’ll just sell the rest,” he said.

For all he’s been through, Drimalas is one of the lucky ones. Two of his neighbors, both in their 80s, drowned in Sandy’s floodwaters. Drimalas may be saying goodbye to his home, but he gets to start again.

Source:

http://www.npr.org/2014/10/29/359873662/after-the-waves-staten-island-homeowner-takes-sandy-buyout

Oct 29

Fox Beach fades to green After Superstorm Sandy, Staten Island neighbors give their homes to Nature

Patti Snyder was 8 when her family moved into a white bungalow a stone’s throw from the sea. Her Italian immigrant father wanted his children to have the opportunity to regularly enjoy what for years he had known only on vacations.

Located in the borough of Staten Island in New York, Fox Beach was the sort of neighborhood where teachers, firefighters, cops and sanitation workers could have their own version of the good life, digging for clams on Midland Beach, fishing for stripers off the pier. Snyder and her brother wanted the same life for their children, so they stayed put, with her brother, Lenard Montalto, raising three daughters in the house he grew up in, Snyder raising her family in a house just down the block. When her daughter moved out of the house, she bought a house on the same block.

Two years ago, Superstorm Sandy changed everything. While Snyder and the rest of her clan evacuated, Montalto stayed behind. Previously in wild weather, their house had taken in a few inches of water in the basement, and he wanted to make sure the pump worked.

When the floodwaters receded, he was nowhere to be found.

After two days of frantic searching, authorities found his body in the basement of the house that had been the lodestar of three generations. He had drowned.

So when Snyder’s house was demolished this summer, she was ready. So were her neighbors. Forty homes in Fox Beach were razed last year, and 200 or so houses will follow — all part of an extraordinarily well-wrought grass-roots campaign to push the state government to buy their homes and return Fox Beach to nature.

If a house is standing in Fox Beach now, it will have a notice of demolition stapled to the front door, with boards over the windows.

“When I first saw all of the homes boarded up like that, I thought, ‘My god, what have we done?’” Snyder says. “But it was the right choice. When we found my brother, I knew that I would never go back. No one should live out there.”

(Previous coverage of Fox Beach)

Joseph Tirone, a local real estate developer who owned a parcel on Fox Beach Avenue, took the lead researching recent buyout cases due to flooding in upstate New York and Nashville, Tennessee. He says a visit to Fox Beach by then–City Council Speaker Christine Quinn made it clear that city assistance might be slow.

But it became clear that New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s history as Housing and Urban Development (HUD) secretary of might play in Fox Beach’s favor, since he had experience with disaster recovery. About a year after Sandy, the state utilized community development block grants (CDBGs) and HUD money to purchase the homes at prestorm prices as part of the Hazard Mitigation Grant Program (HMGP).

In 2016 the Federal Emergency Management Agency will rewrite the national flood insurance maps, doubling the number of households in the New York metro area that fall within the 100- year-flood zone. For those living in areas considered at high-risk for flooding, insurance will be mandatory and expensive as premiums are set to rise, as per the controversial Biggert-Waters Flood Insurance Reform Act of 2012. What this means for low- to middle-income residents living in flood-prone areas remains to be seen.

The federally administered HMGP was designed to reduce the loss of life and property in the face of regularly recurring natural disasters. Whether the rising sea level qualifies as a regularly recurring disaster is still unclear. Over the past five years, the federal government has spent more than $77 billion dollars on addressing climate change, and yet Congress still hasn’t passed a major piece of legislation to deal specifically with the effects of rising sea levels.

As a result of ocean warming and melting ice sheets, over the next 40 years, the ocean around New York City is predicted to rise anywhere from 11 to 31 inches, doubling the number of city residents vulnerable to flooding and greatly increasing the risk to those living in areas that already flood. HMGP grants are being used, albeit in what some say is a frustratingly piecemeal fashion, throughout the city to either provide money to elevate and floodproof existing structures or to purchase homes in high-risk communities so that they can be demolished and the land returned to its natural state.

Oct 20

Oakwood Beach: Sell out, tear down and leave

While many city neighborhoods hit by Hurricane Sandy have yet to rebuild, Staten Island’s Oakwood Beach is returning to its original state at breakneck speed.

That earlier condition, however, is the uninhabited marshy lowlands of the type that greeted Giovanni da Verrazzano, the first European to cross the narrows between Brooklyn and Staten Island 500 years ago.

“It’s really mind-boggling,” said Joseph Tirone, a Staten Island resident who led the push for the state to buy out homeowners and turn the area into a nature preserve and bulwark against future floods. “They’ve done over 50 demolitions already.”

For some homeowners who advocated building back, the buyout seemed like a defeatist approach. Residents of a swath of Oakwood Beach, however, the first community to sign up for the state buyout, sold their small homes and bungalows at pre-storm prices. They have moved on with their lives, spurring neighbors frustrated with the rebuilding process to follow suit.

As Crain’s reported last year, Mr. Tirone learned about the buyout offer then taking shape just a few weeks after the storm. Curious, he sought advice from people in Tennessee and upstate New York who had lived through similar disasters and had successfully turned to a FEMA Hazard Mitigation Grant Program for help. On their advice, he skirted the city government’s still inchoate recovery and, instead, with his neighbors’ overwhelming support, completed reams of paperwork and put his fate and theirs in Albany’s hands.

A few months later, Gov. Andrew Cuomo announced he would seek funding from Washington, D.C., to complete the Oakwood Beach buyout—making the area the model for a greener, safer post-Sandy Staten Island. Of the 184 homes in the buyout zone, all but about 40 have taken the deal. Those left over are dealing with problem mortgages, and have voiced interest in a buyout.

Buying into a buyout

“The federal buyout program never anticipated a whole community being bought out, but the utter devastation of our area called for that,” said Mr. Tirone, who is now running for state Assembly.

To sweeten the deal, Mr. Cuomo created an “enhanced zone” within the buyout program that included a 10% cash bonus for homeowners who participated. It worked.

“People on the fence about selling just put blinders on and took the opportunity to get out,” said Mr. Tirone.

Their neighborhood on Staten Island’s southeastern shore today looks somewhat post-apocalyptic. Some lots are empty. Others are in various states of decay. The remains of a white-shingled house on Kissam Avenue sags in on itself behind an orange plastic fence. Six-foot-tall reeds encroach upon it from either side, brushing the boarded-up windows in the gentle breeze coming off the nearby Atlantic Ocean.

With the state cutting checks for dilapidated houses and Oakwood Beach’s transformation moving ahead, it didn’t take long for people in other hard-hit areas to start asking about selling out.

“I thought what happened over there was great, but it was hard for me to appreciate that while my own neighborhood was still totally destroyed,” said Frank Moszcynski, a resident of Ocean Breeze, just a mile and a half north of Oakwood Beach.

Residents there said that city officials who went on to establish the Build It Back program came to Ocean Breeze in November 2012 and pledged to buy back homes, but only at reduced, post-storm prices. It was not a great deal, but it was better than nothing.

“They said they’d be back tomorrow with paperwork to get things started,” Mr. Moszcynski recalled. “Tomorrow never came.”

Joe Herrnkind—a neighbor of Mr. Moszcynski who was unable to get back into his house for three days and who discovered that the floodwaters had gone as high as his attic—was similarly frustrated by what seemed to be the city’s ham-fisted response. In the spring of 2013, they formed the Staten Island Alliance, a community group focused on getting relief for the area around Ocean Breeze. Inspired by what had been done at Oakwood Beach, Mr. Moszcynski inquired about the state buyout program, only to be told by a local city official, “I think we can both agree that ship has sailed.”

Neighbors organize

Undeterred, Mr. Moszcynski began to ask around. A few weeks later, a mutual friend introduced him to Mr. Tirone, who assured Mr. Moszcynski that the buyout program was very much available to those who knew how to apply.

Playing the role that community leaders in Tennessee and upstate had played for him, Mr. Tirone guided the alliance through a bureaucratic maze.

Ocean Breeze homeowners responded much like those in Oakwood Beach had. Messrs. Herrnkind and Moszcynski on weekends set up a tent in their neighborhood and urged neighbors to sign a petition urging the governor to buy them out. More than 90% did, and on Nov. 19 of last year, Mr. Cuomo stood next to the tent and told the community that the buyout would go forward.

“I hadn’t seen that many smiles since before the storm,” said Mr. Moszcynski. “There was finally some sense of hope around here.”

After that press conference, buyouts started in Ocean Breeze, and Mr. Cuomo has again used the enhanced zone idea to increase the participation rate, helping to return this quiet community to nature.

“People here are happy with the buyout,” said Mr. Herrnkind. “We’re moving on with our lives a lot faster than the people in Build It Back.”

Correction: City officials who eventually established the Build It Back program visited Ocean Breeze in November 2012. This fact was misstated in an earlier version of this article, originally published online Oct. 20, 2014.

A version of this article appears in the October 20, 2014, print issue of Crain’s New York Business.

Source:

Oct 16

Retreat from the Water’s Edge BY NATE LAVEY

Nearly two years after Hurricane Sandy, New York has begun a “managed retreat” from some low-lying areas that are vulnerable to flooding and storm surges. Many residents of the Oakwood Beach section of Staten Island have opted into a program that allows them to sell their homes at pre-Sandy value, to the State of New York, which intends to return hundreds of parcels of land to nature. The cleared neighborhood will then serve as a buffer zone to protect other parts of the island. The program has been extended to other areas of Staten Island and Long Island that are at continued risk of flooding in the face of climate-change-related events. In this video, residents describe their experiences with the buyout program, and urban planners explain why communities along the East Coast need to consider moving away from the water’s edge.

The video can be seen in the link below.

Source: http://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/hurricane-sandy-retreat-waters-edge

Apr 06

State Expands Sandy Buyout Program to Graham Beach

The state is expanding its buyout program to a third Hurricane Sandy-affected neighborhood on Staten Island.

The state’s enhanced buyout area will now include Graham Beach on the island’s east shore.

Under the program, homeowners who had their properties wiped out or heavily damaged by Hurricane Sandy can receive the pre-storm value of their homes plus incentives.

The state will then use the property to maintain the island’s shoreline.

State officials have already started buyouts in nearby Oakwood Beach, buying 170 properties at a value of approximately $70 million.

Another 130 buyouts are pending in the Ocean Breeze neighborhood.

Watch the video at the link below.

Source: http://statenisland.ny1.com/content/news/206513/state-expands-sandy-buyout-program-to-graham-beach

Apr 04

S.I. Homeowners Hope Buyout Committee Will Spur Action

NY1 VIDEO: A group of homeowners on Staten Island who submitted an application for state buyouts months ago but have yet to hear back have formed a committee in hopes of getting Governor Andrew Cuomo’s attention. Watch the video at the link below.

Jan 29

In a Global Warming World: Protect and Rebuild or Retreat?

Hurricane Sandy decimated coastal communities. Now what?

The Far Reach of Our Coasts — and Coastal Problems

While less than 10 percent of U.S. land area is coastline (excluding Alaska), “123.3 million people … or 39 percent of the nation’s population lived in” shoreline counties in 2010, according to the federal government. Put differently, our coasts, “substantially more crowded than the U.S. as a whole,” have a population density more than six times that of inland counties.

So our coastlines are well populated if not downright packed, and that spells trouble [pdf] whenever big storms come a-knockin’ — the kind of trouble that often lingers long after blue skies return. Now add to that climate change with increasing storm intensity and sea levels projected to rise by about three feet by the century’s end, and you’ve got yourself a real problem without an obvious solution. Do you rebuild after every storm and flood, hoping you can fortify the new infrastructure to survive the next one? Or do you give up and retreat to higher ground?

Such questions are especially palpable for New Yorkers and New Jerseyites who live (or lived) along the destructive path ofSuperstorm Sandy, a mammoth storm that barreled up the Atlantic coastline in October 2012. Sandy-decimated communities must now decide what to do. Some say “rebuild,” and the federal government has put substantial funds into such efforts post-Sandy. Others, like New York Governor Andrew Cuomo, argue that certain coastal communities should recognize the inevitable and retreat to higher ground. Federal dollars [pdf] are also substantially funding this choice.

So which response makes the most sense? It’s a question of vital importance and not just for New Yorkers and New Jerseyites. How these communities respond to Sandy will be instructive for the myriad of other communities that must decide how to respond to the new normal coming courtesy of climate change. Interestingly, both approaches are being pursued. Let’s take a look.

A Case for Retreat

Hurricane Sandy, according to Governor Cuomo, damaged “[a]s many as 300,000 homes across the state … and approximately two-thirds of all properties flooded by Sandy were not covered by flood insurance.”

Joe Tirone’s house on Staten Island, ready for demolition. Tirone’s house was part of the state’s buyout plan. (Joe Tirone)

In the aftermath of such devastation, last year the governor effectively offered New York property owners whose houses had been devastated by Hurricane Sandy a deal: sell their property to the state for its pre-Sandy value, and the state would turn that land into greenspace intended to provide protection to inland communities from future storms. For a number of New Yorkers, including 319 Staten Islanders in the Fox Beach neighborhood of Oakwood Beach, that was an offer they couldn’t refuse — as of this writing, according to Joe Tirone, a Staten Island real estate broker and Fox Beach property owner who helped organize the Fox Beach buyouts, 310 homeowners have filed buyout applications, 258 have received offers from the state, and 100 have completed their sales.* And the demolitions have begun.

For Tirone, Sandy changed everything.

It “knocked everybody back on their heels,” Tirone told TheGreenGrok. “Everybody had just finished their renovation from Irene … and then, a month or two later, this storm comes and that was the knock-out punch. The one where they just said, ‘I can’t do it anymore.’”

The 11-foot flood line on Tirone’s one-story, one-family rental property would have meant a complete gut renovation.

“There was nothing that was really salvageable, and if I were to rebuild it, I probably would have ripped the siding off as well because of mold,” said Tirone. “In case the buyout didn’t work, I was ready to fix it up again and rent it for awhile and then sell it eventually. But thank God, I didn’t have to do that.”

While prepared for the worst, Tirone took action when he heard about the buyout plan, attending meetings, researching the program, and organizing his neighbors. (See video about Fox Beach from May 2013.)

As it turned out, Fox Beach was a good candidate for the buyout and greenspace restoration. It’s located in the middle of theBluebelt stormwater management system, which includes “15 watersheds clustered at the southern end of the Island, plus the Richmond Creek watershed … conveying, storing, and filtering stormwater.” Through this project, the state will be able to restore the area to its natural wetland status improving the ecosystem services provided by the Bluebelt.

But while Tirone and his neighbors seek higher ground, with assistance from the feds and the state, New York City is planning to hunker down.

Bloomberg on the Waterfront: ‘We Must Protect It, Not Retreat from It’

When it comes to solutions to problems posed by Sandy and the like, former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg had a lot of them. As well he should: increasing storm intensity and sea level rise pose enormous challenges to the city. “We expect that by mid-century up to one-quarter of all of New York City’s land area, where 800,000 residents live today, will be in the floodplain,” Bloomberg said last June. ”

If we do nothing, more than 40 miles of our waterfront could see flooding on a regular basis, just during normal high tides.”

The former mayor has spoken in favor of limited retreat as well as the development of natural buffer zones. And he has called for expanding the Bluebelts, which have been “incredibly successful at absorbing floodwaters in Staten Island,” he said. But with 25 percent of NYC’s land area threatened by flooding, it’s not surprising the Bloomberg administration’s main strategy for a future sustainable city is more about rebuilding and protecting rather than retreating.

Consider, for instance, that a full-bore retreat would mean abandoning such historic sites as Ground Zero — a scenario that any New Yorker, let alone a mayor, would find hard to stomach.

It Ain’t Cheap

Bloomberg’s plans are detailed in “A Stronger, More Resilient New York” [pdf], an in-depth report that includes 250 concrete recommendations to better protect the city from storms and other impacts expected from climate change.** The report lays out a strategy for holding on to most of the city’s coastal communities through “a combination of permanent elements and flexible flood protection systems” (i.e., “a system of strategically placed floodwalls, levees and other features [that] would provide a strong line of defense against flooding”). Bill de Blasio, New York’s new mayor, has indicated he is onboard with the path Bloomberg blazed in this area — a path carrying a price tag of almost $20 billion.

I have to say, the 400-plus-page report (along with the environmental initiatives outlined in Bloomberg’s PlaNYC and theprojections by the NYPCC2 [pdf]**) reflects a very careful, thoughtful and sophisticated assessment of the threats to New York City and how to protect it and its residents from those threats.

The question in my mind is, assuming that all the flood-protection infrastructure gets built, what happens if things turn out to be much worse than what is being projected. What if the flood barriers fail and the city is inundated by another storm? (These types of failures do happen — think the New Orleans flood during Katrina) Does the city rebuild yet again (as New Orleans is doing), and construct even greater protective barriers? And who pays? (See this recent New York Times article on the costliness of putting off dealing with climate change.) And what happens to the people in harm’s way? I don’t recall seeing those issues addressed in the mayor’s plan.

I hate to think of this, but it could be that decades from now people will look back on the rebuild decisions made by New York City, New Orleans and the like as prime examples of denial. On the other hand, smart rebuilding could turn out to be visionary and innovative steps into a globally warming future. Let’s hope it’s the latter.

________________

End Notes

* As of this writing, according to Joe Tirone, who helped organize the buyouts, there was one holdout in Fox Beach and several had not accepted the state’s offer for their home. There were 184 homes in the first phase of the area’s buyout; a second phase added another 135 Oakwood Beach homes to the plan.

** The report was informed in part by the work [pdf] of the New York City Panel on Climate Change (NPCC2) that Bloomberg empaneled “to study the effects of the changing climate on a metropolitan region” and that “developed New York-specific climate projections.”

Source: https://blogs.nicholas.duke.edu/thegreengrok/in-a-global-warming-world-protect-and-rebuild-or-retreat/

Jan 20

After Sandy, Staten Island Community Chooses State Buyout

As demolitions begin, Staten Islanders still grappling with reality of returning land to nature

NEW YORK—Under gray skies last Thursday morning in Staten Island’s Oakwood Beach, the fifth home in this neighborhood to be demolished under the state’s buyout program gave way to the claws of an excavator.

First the garage was flattened. Next, the chimney of the house was ripped down and smashed. Then the back door and back wall of the one-story bungalow came off and the shingled roof was stacked atop the growing pile of wood and cement.

The home was once full of life, and its residents part of a community where people knew their neighbors. They walked their dogs and rode their horses on the nearby beach. They sat on their back porches in the morning with a cup of coffee and listened to the birds sing. All of that is rapidly becoming just a memory.

The demolitions in Oakwood Beach last week, one on Thursday and one on Friday, are the unofficial start of a process of returning the area to nature under a buyout program funded by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development and administered by the state’s Community Development Block Grant Disaster Recovery.

Superstorm Sandy’s havoc brought three deaths and 6 feet of storm surge and flooding to the Staten Island neighborhood. Some homes were lifted clean off their foundations and deposited in nearby marshland.

Like other hard-hit areas of New York City, residents started rebuilding, and tried to move on with life. But in early 2013, some realized they could appeal to the state to buy their homes so that they could afford to live somewhere else.

In order to qualify for a buyout a majority of the 319 homeowners in the area needed to be in agreement. Eventually, even those who were resistant went along with the plan. To date, there are only nine homeowners who haven’t taken part.

“It was never the intention for us to include the entire neighborhood,” said Joe Tirone Jr., the head of the Oakwood Beach Buyout Committee, of the process that he helped organize. “The government … recognized the need.”

But signing on to the plan seemed to make sense.

Now listed in the 100-year floodplain, Oakwood Beach faces the threat of massive flood insurance premium rate hikes that could go up to $20,000 per year within the next two years, too much for most middle-class households. And there is always the very real possibility of being flooded again.

Oakwood Beach sits at just 5 feet above sea level, and is situated in a bowl-like natural setting without sufficient natural or man-made drainage systems.

The governor agreed to buy the homes at pre-storm market value so the land could be returned to its natural setting of marshland and tall grasses. It was reasoned that future property losses would be averted, and the reclaimed land would act as a natural buffer against flooding.

“Those homes shouldn’t be there in the first place,” said Salvatore Parello, owner of the small house at 88 Foxbeach Ave. that was demolished last Thursday. He was not on site to see it go, but was reached by phone.

He described his experience of owning the house for 40 years as: “There was problem, problem, problem. Make a claim, make a claim, make a claim.”

Representatives from the governor’s Office of Storm Recovery (OSR) estimate the cost of buying out the 310 homeowners will be at least $100 million.

The amount that each homeowner is paid varies according to the pre-storm value of the home. The average price paid for the homes is about $400,000, while one of the largest offers for a buyout was just over $710,000.

Parello said he was happy with what the state paid him, but would not disclose a specific dollar amount.

“It was the right thing to do,” he said.

As of Jan. 19, 98 residents have sold their homes to the state, and 122 have signed contracts but not yet closed on the sales. Thirty-eight homeowners have been made offers, but have yet to sign contracts.

The state estimates that in the weeks ahead, they will see an average of 10 closings a week. As soon as a deal is closed, the formal permitting and inspection process leading to demolition begins.

To Stay or Go

The governor’s office has faced questions over prospects for the few homeowners who decide to stay in the neighborhood. Barbara Brancaccio, a spokeswoman for the OSR, admits it was a tough decision for residents, but that they approached the state and not the other way around.

“The important thing to note is that it was their decision,” said Brancaccio at the demolition site last Thursday. “The people here came to the governor in nearly 100 percent consensus and essentially said, ‘We all want to leave.’”

As the buyout is voluntary, residents who stay will not be subjected to eminent domain and will still have regular city services. There will just be vastly fewer homes.

“There are other options—if people want to stay, they can stay,” said Brancaccio. “Some people might like having more space [around them].”

Not all residents are in agreement, or as clear about leaving, though. Some would rather not go anywhere.

“It’s a gamble either way,” said one homeowner, who asked not to be identified because she is among the 258 owners who have received offers from the state, but have not closed on a deal.

“From day one, a third of us didn’t want it,” the homeowner said.

As the neighborhood empties out, it is increasingly clear that people who do choose to stay might see the value of their homes drop. It might also be difficult to sell a home in an area overrun with idle land. The community is virtually gone.

“It’s horrible,” said the homeowner, “When you look at the whole picture, there’s no way to stay.”

Natural State

These days, Oakwood Beach is beginning to resemble a ghost town.

Rows of neat houses—many petite, one-story bungalows—are already empty, with boarded-up windows, fenced-off yards, and signs warning against unauthorized entry and alerting for the presence of rat poison.

The impact of the overall scene makes the few occupied homes with potted plants, front porch lights, and cars parked out front seem out of place.

For Parello and the 98 other homeowners who have already closed on sales with the state, the days of living in fear of flooding and rebuilding are over. As homes are taken down and debris is hauled away, the ground will be cultivated and seeds for native grass and plants will go in.

Chris Hutchins, a project manager with the state’s NY Rising Community Reconstruction Program in the governor’s office, said at the site of the demolition Thursday that the work happens quickly. Just across the street there was recently a house, and now there is just dirt.

“You’d never know a house was there,” said Hutchins.

Representatives from the governor’s OSR said there are at least six demolitions scheduled for the week of Jan. 20, and demolitions on the remaining homes purchased by the state will proceed quickly.

Source: http://www.theepochtimes.com/n3/459607-after-sandy-community-chooses-state-buyout/